It’s taken five years for Pablo Clark to design and refine and illustrate The Old King’s Crown, his very first board game. Over that time, whispers have been growing among playtesters and convention crowds that this title, where players take the role of asymmetric factions competing to win the rulership of a fantasy kingdom, was something special. Something, certainly, that was better than we had any right to expect of a first-time designer. Now after a self-publishing Kickstarter run, it’s finally here, and we can explore Clark’s kingdom in all its glory.

What’s in the Box

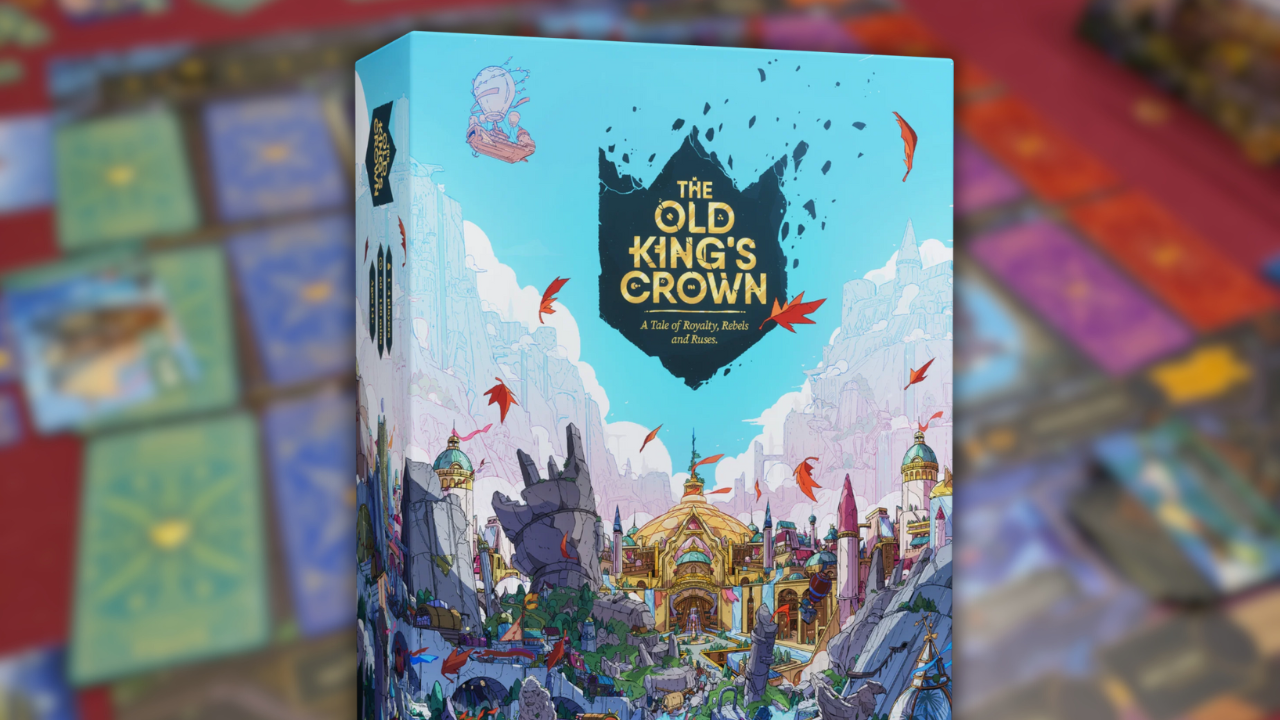

There’s no discussing The Old King’s Crown without first talking about the art. It’s right there on the box lid, after all, and it is stupendous. Rich with color and detail, stylized yet recognizable, bringing to life in glorious precision a world that has never existed. The fact that the designer is also the artist just makes you wonder how he got to the front of the queue when talent was given out.

Even when you slide off that sumptuous box lid, the art is everywhere within, almost every picture adding to the story and the setting. It’s on the board, which is a window from a high tower looking down on the provinces of a kingdom in civil war, as though players are plotting in their fastnesses while the people suffer. It’s on the deck of tarot-sized cards for each faction, filling in the wide narrative gaps in the brief rundown given to the setting in the rulebook. It’s on all the kingdom cards, faction-neutral buffs available for players to pick up. And it’s all astonishing: every time you play, you’ll notice something new.

All the graphic design and component quality here is sumptuous and spellbinding. The layout of the rulebook with its pictorial examples, the way the board carefully walks you through the stages of each turn, the pleasing color and layout of each faction’s markers and central board, embossed with pockets to hold cards and chunky, printed wooden pieces of the matching color. The remaining few generic items: a turn marker, clash order markers and a few other bits and pieces are simple black-and-gold wood.

Assembled as a whole, it takes up a massive chunk of table space – but it looks incredible, a wood-and-cardboard invitation to stop and stare, a whole world laid out in squares and circles for those who take the time to look and appreciate.

Rules and How It Plays

This is quite a complex game, but the complexity is in the sheer information density available rather than the core flow of play, which is relatively straightforward. Games last a fixed number of turns, normally five, and each turn is broken down into four seasons. The meat of proceedings takes place in summer, where players will fight over three locations, each of which has two possible rewards, to be chosen by the victor. First, in turn order, players place their herald into one of the victory spots, which will bring them bonus points if they win there. They can then place some of their small pool of supporters in a location, which provide a small combat bonus. Then it’s time for the card play.

All players start with functionally identical card decks from which they draw a hand of six. Everyone places a card, face down, next to each location. Then they’re resolved one at a time, with everyone flipping over a card and adding the number on that card to the number of supporter pieces there. Highest total wins. Except, very often, it doesn’t.

The reason for this is that many cards have action icons which can be invoked to complicate matters. Ambush, for example, lets the owner play a second card into the melee. Flank lets that card slide out of the current combat and into a future one. There are others, but most terrifying of all is Deadly, which takes place after all other actions and kills enemy cards, putting them out of the game and into the dreadful “lost pile” for the remainder of play unless they have a helmet or shield icon, the latter of which also keeps them in the fray for that location.

It’s hard to overstate quite how taut this is. Someone flips the cards and all at once everyone’s craning over the massive board, desperate to decode the game’s intricate array of symbology to work out who’s in contention and what the next steps might be. Combats that are decided by ambush, or value ties which are resolved with additional card play, crank the excitement up even more, as do deadly attacks which can see critical cards assigned to the lost pile forever. And then when it comes to heralds, the stakes just go through the roof.

All the locations score you influence, the game’s name for victory points. But if you win in a space where you’ve placed your herald, you get an extra point. And if you win in a space where you and others have placed their heralds, you get to take a victory point off each of those poor unfortunates. This is a game where a winning tally can be 15-20 points, so actually taking points off other people to add to your own is huge. A well-calculated herald placement can swing you from last place to first in one fell swoop, ensuring that everyone is in contention, right up until the end.

Naturally, this invites all kinds of scheming. Discard piles are public information, so you can grub around in people’s trash, seeing if they’ve played that deadly card or whether it might be lurking in their hand, still, to screw you over. It’s also possible for players to buy additional cards to add to their deck, which not only come from asymmetric stacks tailored to your faction, but can add even more wrinkles to the formula, like making it lowest card wins instead. You’ll need to keep an incredibly sharp eye on what everyone else is doing if you want to minimize the chance of nasty surprises.

Buying new cards is only one way in which the game’s asymmetry shows. Each faction has a set of four special one-use powers, plus a fifth that you can invoke if you win a particular location. They’re all unique, and roughly aligned to that faction’s thematic play style. The Gathering, which represents the cult-like state religion, can swap the positions of two cards in combat, or sacrifice cards into the lost pile in order to gain resources to buy more cards. The uprising, by contrast, which is a revolution of the state’s common folk, can give cards the deadly effect, or the retreat effect.

As you begin to weave together the various unique card effects, asymmetry, special powers, and location victory effects you can begin to see all sorts of ways you can influence not only individual clashes but the game state as a whole. Your hand size will drop as the game progresses, except you can arrange things so it doesn’t. You’ll lose supporters, unless you find a way to gain them back. If you buy enough new cards you’ll get a point bonus, but you’ll have to make big sacrifices to do it. The number of ways you can approach The Old King’s Crown and still win is absolutely jaw-dropping, almost mind-crushing in its loops within loops within loops.

And still there’s more! We’ve only really covered the summer turn so far. In spring, players use cards to bid in a selection of kingdom cards, most of which are game-breaking in their own right. They can let you swap cards you’ve drawn for one in the lost pile, steal other player’s special powers, or give your cards extra effects. Each is easily enough to build a strategy around by itself, but you can hold up to two of them. Except that after the initial bid, you can steal kingdom cards off other players instead of taking a fresh one, forcing them, and you, to replan on the fly.

In the autumn you can send cards journeying, which gives you the chance to buy more cards, or you can send them to council, where they stay and give a long-term special ability. This can mean potentially more points if you win with your herald, the chance to grab supporters back, or other effects. Finally winter is just a bookkeeping phase and, frankly, a chance to catch your breath after the absolute strategic and social insanity of an entire round of The Old King’s Crown.

This is not an exaggeration. While there’s a staggering amount to enjoy here, the sheer quantity of detail you need to take into your stride to maximize your chances is almost overwhelming. You need to be on top of your own special powers and special cards, along with everyone else’s, what they’re buying, what they’re playing, what’s in their discard pile or the lost pile. You need to be cognizant of each player’s kingdom cards, what they do and what you need to bid to steal them, or protect your own. Initially this seems impossible. It gets easier with practice but you’ll need to play an incredible amount of this game if you want to properly internalize it.

You don’t, however, need to do all that in order to win. It’s perfectly fine to play from the hip more, although the reams of detail will nag at the edges of your thought processes as you do so. And you can get away with it because, fundamentally, you can check every discard pile in the game and still not be certain whether a player has just thrown down their deadly card into a herald location or whether it’s a tricky bluff. You can do very well just by reading faces, voices, and body language. And that creates a strange tension at the heart of The Old King’s Crown: it’s a game that gives you the most astonishing range and leverage to build strategies, and then lets other players pull the rug out from under you with a cunning bluff.