Just like how classic rock suddenly means Linkin Park and Smashing Pumpkins instead of Jimi Hendrix and The Doors, the fact that the best retro games of all time now has to include PlayStation 2 and Xbox games is existentially frightening, but ultimately a testament to just how much the games of the present owe to the trailblazers who finally had 3D toys to play with and still turned out masterpieces that hold up to this day. That’s to say nothing of their forebears in the NES/Genesis era, even the Atari. The history of gaming is becoming long indeed, and anyone serious about the medium owes it to themselves to pay homage to best the past has to offer. We just went through the trouble of showing you the best place to start on every single major console.

Atari – Breakout (Atari, 1976)

Super Breakout for Atari 2600

Sure, history will always look upon the ancient heyday of video games with kindness, but real talk, there’s not a whole lot of from the 70s that folks are playing in anything but an academic sense in the present day. And when it comes to the console leader of the pre-NES era, that’s an even bigger question, mostly answered by cricket noises. The best Atari games will always be worthy of respect, but playable they’re largely not. However, there’s something to be said for the power of simplicity. There’s a reason Pong is still playable to this day while you might have to fast-forward a decade or so to get to another decent Tennis game. And with that in mind, Super Breakout on the 2600 is the winner almost by default: an enhanced version of an already excellent game with a deceptively simple premise–racquetball, where you’re trying to destroy the wall–drowning in features, new game elements (trapped balls, a moving wall of bricks, co-op), even including the original Breakout as a bonus for those who don’t even need the bells and whistles.

NES – Super Mario Bros. 3 (Nintendo, 1988)

Super Mario Bros 3 on NES

Super Mario Bros. 3 was legendary before it even released outside of Japan, thanks to The Wizard hyping up every kid across the planet, a campaign of cultural domination that even bled into Nintendo’s marketing at the time. That’s the part you can chalk up to Nintendo’s PR team absolutely crushing it in the late 80s and early 90s. But the fact that Mario 3 still feels just as fresh and intricate and vast as it did the day it released? That you can chalk up to just pure old-fashioned brilliance. Even on a system with a library as enormous as the NES, Mario 3 is a masterclass in elegant game design, in far thinking ideas, in secrets for secrets’ sake, in pure digital joy. The ways this sends the bedrock ideas from the original Super Mario Bros. into the stratosphere within a mere five years is downright miraculous. The ideas that Mario 3 would introduce are still in play when it comes to new games in this series, from every new game getting a new animal suit, to the overworld map full of secrets becoming a standard framework for platformers. The only thing giving away its age in any way is the 8-bit graphics.

Sega Master System – Phantasy Star (Sega, 1988)

Phantasy Star on Sega Master System

At a time when every Western RPG was taking its cues from Lord of the Rings, Phantasy Star was one of the first to look to Star Wars for inspiration, becoming one of the first Japanese RPGs to take the leap where no man has gone before. But even just a year after Final Fantasy established itself in the hearts and minds of gamers, Phantasy Star was pushing the envelope to the breaking point. It had a plot that spanned an entire galaxy of planets, big, beautiful character sprites instead of the stubby avatars of the Dragon Quests and Ys games of the time, and most impressive of all, fully first-person 3D dungeons. But more than this, the story took some serious risks, being one of the few titles at the time with a female protagonist, the determined Alis gathering a posse to dish out vengeance on the wizard who killed her brother. Phantasy Star isn’t just the best Master System game, but a one giant leap ahead for RPGs as a genre.

TurboGrafx-16 – Air Zonk (Red Company/Naxat Soft, 1992)

Air Zonk on Turbo-Grafx 16

The TurboGrafx wasn’t able to snare too much attention away from Nintendo and Sega’s knock-down-drag-out war of the early 90s, but it did allow them to make the bigger, weirder choices neither company would. Imagine Nintendo teaming with CD Projekt Red and doing a bespoke kid-friendly Mario-branded take on Cyberpunk 2077, and you have a faint idea of just how bizarre it was for Hudson to take Bonk, their beloved massive-headed mascot character, and stick him in a cartoonish cyberpunk mayhem world for a side-scrolling shooter. Air Zonk may be one of the shortest games on the TG-16, but sincerely one of the best games on the system. Even compared to many of the SNES games that would come after, it’s got some of the strongest, eye-catching art design of the era, in service of some of most chaotic gameplay. Like the TurboGrafx-16 itself, Air Zonk was here for a good time, not a long time.

Genesis – Phantasy Star IV (1995, Sega)

Phantasy Star IV on Genesis

When talking about RPGs in the mid-90s, it’s hard to argue against Square being the reigning, undisputed champions of the genre. But Sega’s crowning achievement on Genesis is a title that belongs in their hallowed company. Phantasy Star IV was the final single-player game in the series, and just like its forebear on the Master System, its legendary developers pushed the Genesis to its absolute breaking point, from the heavy reliance on manga-style panel storytelling, to the elegant macro and combination spell systems that are still rare to see in RPGs even these days, to the ambitious traversal options taking the original Phantasy Star’s space travel to its logical apex. But more than all that, the story is still breathtaking to this day, not just tying into the multiple generations of Phantasy Star heroes that had gone by at this point, but a tale unafraid to throw in twists and turns on par with anything Square was doing with Final Fantasy at the time. That includes the unexpected, heartbreaking death of a major character that beat the death of Aerith to the punch by a few years. The Genesis wasn’t known for its extensive RPG library, but it’s still home to one of the greatest.

Sega CD – Snatcher (1994, Konami)

Snatcher on Sega CD

For much of the West, Hideo Kojima didn’t become a household name until he went fully Hollywood making blockbuster filmmaking and ambitious stealth video game mechanics meet in Metal Gear Solid. But those few, proud Sega CD owners out there willing to take a chance on a point-and-click cyberpunk adventure were ahead of the game by a few years. Even more than in Metal Gear, Kojima’s influences are pretty blatant, with the plot and character designs only just barely filing the serial numbers off of elements of Terminator and Blade Runner. But there’s still a magic all its own, an intricately-built world with scientific advancements and political flashpoint events that feels plausible and lived in. Even with Kojima’s trademark quirks at play and some of the weirder/cringier bits sanded down for the Sega CD–never Google how old Katrina was in the PC-88/MSX ports–there’s still a pathos to every character far beyond much of what was being produced at the time. Granted, the folks who owned a PC-88 or MSX in Japan were even further ahead of the curve, but even there, the Sega CD port got a few extras that never wound up in any other version, as well as an English dub that, while not Oscar level, is a revelation compared to most voice acting all the way up through the PS2 era, and made the story of amnesiac robot-hunter Gillian Seed all the more memorable for the time.

32X – Virtua Fighter (1995, Sega)

Virtua Fighter on 32X

If Sega had actually bothered to support the poor, doomed (pun unintended) 32X, it could’ve been a contender, and the fact that Sega actually managed to get a damn fine port of one of the most advanced fighting games of the time crammed feature-complete into a 32X cartridge is proof positive there was juice in Sega’s ill-fated add-on. Hell, lest we forget, there was a brief window in which the Saturn port of the original game was a sloggy, glitchy mess, forcing Sega to release a free updated version called Virtua Fighter Remix a few months after. And remember, kids, this is ages before day-one patches became a thing, they had to issue Remix by mail. The 32X port may not have been as pretty, but it played just fine, and even had a Tournament mode the Saturn didn’t. For a hot minute, you didn’t have to go to the Saturn to get welcomed to the next level. You could have it on a cartridge.

SNES – Final Fantasy VI (1994, Square)

Final Fantasy VI on SNES

As always, the Best SNES Game Ever winner is a coinflip decision between Final Fantasy VI and Chrono Trigger. Within the course of a year, Square had completely changed the game for RPGs between those two games, but for Final Fantasy in particular, FFVI represented the sum total of all lessons learned over the course of seven years making 2D turn-based titles. Every element of the game absolutely sings, and that’s very literal when it comes to the full-fledged opera sequence they managed to squeeze into the middle of the game. Had the game ended in its first act, with our heroes heading to a floating island to defy a despot, you’d be looking at one of the best RPGs the SNES would ever produce. But the game’s second act, having players cope with the complete and total victory of one of gaming’s most despicable villains, Kefka, is where it becomes one of the greatest experiences of all time, with a hero surviving a suicide attempt and using her life to rebuild hope from being firebombed into the dirt. There are still folks who will tell you FFVI is the best game in the series. Absolutely no one will argue against it.

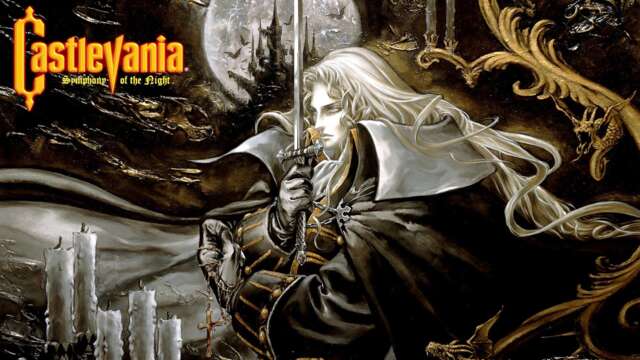

PS1 – Castlevania: Symphony of the Night (1997, Konami)

Castlevania: Symphony of the Night on PS1

There was once a time in gaming history where 2D was a four-letter word. The future was now, sprites were out, polygons were in. But even with all the bangers that the PS1 would eventually produce, a great many of them feel like prototypes, an entire industry touching the future like the monkeys in 2001: A Space Odyssey, and not quite feeling comfortable with the newfound power. There are a slew of games that helped push the medium forward, but not nearly as many worth returning to now that we’ve gotten ahead. Symphony of the Night, however, has remained evergreen, a masterpiece of art direction and game design that didn’t just expand everything we thought of when we think of Castlevania, but quickly became a touchstone genre all its own, the hallowed Metroidvanias that are now ubiquitous in the gaming landscape. And that’s before one gets into the twists and turns of the thing, the endless secrets players are still unearthing nearly 30 years later, the PS1’s sprite scaling being put to genuinely impressive use, the fact that the second half of the game flips the entire castle upside-down. Sony was truly hellbent on burying 2D gameplay with the original PlayStation. Symphony of the Night has turned out to be immortal.

Saturn – Panzer Dragoon Saga (1998, Team Andromeda)

Panzer Dragoon Saga on Saturn

While there’s a long, long list of obscure treasures for the Saturn that never saw Western shores whatsoever, Panzer Dragoon Saga is one of the few that did, and even that wasn’t even remotely enough to draw eyes away from Final Fantasy VII at the time. The story of the Saturn outside of Japan is one tragedy after another, but the greatest is that one of the best RPGs ever crafted remains stranded forever on a dead end console that’s still struggling for respect after all these years. Even compared to Square’s best efforts, Panzer Dragoon Saga takes everything exhilarating about the high-flying Panzer Dragoon games–underrated in their own right for their Space-Harrier-meets-How To Train Your Dragon gameplay–and applies them to a heavy fantasy epic that wouldn’t have an equivalent in tone, maturity, and intensity until Square’s own Final Fantasy XII….eight years later.

Nintendo 64 – The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask (2000, Nintendo)

The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask on N64

It can’t be a particularly small ask when a developer has the unfortunate duty of crafting a follow-up to a game that almost immediately went down in history as one of the greatest video games ever made. So the fact that Nintendo actually made a better, more ambitious, and haunting experience than Ocarina of Time is astonishing. Using all the same mechanics as Ocarina, Majora’s Mask is a game operating with an ever-present time crunch. The end of the world is always three days away, a sinister moon with a psychotic face will be crashing down, and Link must Groundhog Day his way through to not just redeem the poor, possessed Skull Kid, not just save the world, but create a future for the people of Termina worth living in when he’s through. It’s a darker tale than many folks were expecting, but Link’s quest has never felt more meaningful.

Dreamcast – Jet Set Radio (2000, Smilebit)

Jet Grind Radio/Jet Set Radio on Dreamcast

There was once a time where the prospect of playing a cartoon felt completely ludicrous–and no, Dragon’s Lair/Space Ace don’t count. But Jet Set Radio dares to dream so much bigger, with a game that feels like playing inside the mind of graffiti artist, in all its beautiful, neon-colored glory. Part rollerblading sim a la Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater, part graffiti sim, part hyperkinetic remake of Walter Hill’s The Warriors, every single moment of Jet Set Radio radiates cool. The cherry on top is one of the most eclectic soundtracks ever curated, an audio introducing the world to Japanese hip-hop, funk, and punk. Though some folks have tried to recapture the magic, there’s still nothing out there that hits exactly like this.

PlayStation 2 – Shadow of the Colossus (2005, Sony Computer Entertainment Japan)

Shadow of the Colossus on PlayStation 2

This might be hard for some younger gamers to believe, but once upon a time, we used to get into very big, obnoxious arguments about whether video games were art. And while gamers knew inherently that the answer was yes, Shadow of the Colossus would put a button on that argument once and for all. Sure, it’s impressive and exhilarating enough climbing all over some of the biggest digital creations ever committed to a game, but the why of it all, how much of the storytelling had to be found rather than told, and how every mechanic helped to tell that story, those are the factors that can’t be replicated in any other medium. For gamers who already knew the power of the medium, though, even they had to stand in awe of the sheer audacity of a quest that poisons their exhilaration with guilt, and pays off that guilt in spades when our hero Wander completes his quest.

Xbox – Psychonauts (2005, Double Fine)

Psychonauts on Xbox

There’s no genre that suffered more for 2D games going out of style for a time than the humble platformer. While the likes of Mario 64 showed the immense potential of 3D platforming, the best that far too many games would do at the time was create a giant playing field and churn out a collect-a-thon with a cute potential mascot character. Psychonauts, however, would prove to be a turning point for Double Fine, proof positive that with enough imagination and ideas, these big open spaces could play host to so much more. More, in Psychonauts’ case, involved making the collectables meaningful, a integral part of the narrative. It meant cranking up the humor and oddity to undeniable levels, without sacrificing the emotional tale at its center. It meant making every square inch of every stage not just fun to traverse, but to tell more about the characters whose brains we’re jumping around. Its one thing to have a story about a psychic summer camp full of big-headed kids, but another to take the concept seriously, where our hero Raz’s deep seated fears of abandonment mean just as much to the player as it does when you get to level an underwater fish city like a kaiju.

GameCube – The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker (2003, Nintendo)

The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker on Gamecube

If there’s one constant with Nintendo over the years, it’s that you may not always get what you want, but they will often get you what you need. A Zelda game that looked like a Nickelodeon cartoon wasn’t what anyone particularly wanted in the post-N64 period–especially not after that one Spaceworld demo. But it doesn’t take long after taking in the sea breeze as cel-shaded Link and meeting the bratty sea captain Tetra to know this was exactly what the world needed. Without sacrificing an inch of the large-scale adventuring the series had been known for, Wind Waker introduced a lighter touch back to Zelda that had been missing for quite some time, a greater willingness to play around in the world, make it inviting rather than foreboding, all while encouraging players to brave a vast ocean full of treasures and dangers. And when the story needed to lower the boom, it still did so with style, and ever so much joy.